Why global climate negotiations will have far reaching power and impact

Good afternoon!

Today I’m offering a crash course in the global climate negotiations – and why I think the negotiating body has the potential to be the most powerful, far reaching political group the world has ever seen. Yes, this is a big statement. But stick with me for a bit, then drop me a note if you disagree.

-Mike

Imagine if there was a group that could set rules for a new kind of currency, direct trillions of dollars in annual transfer payments around the world, and issue rules for ending the use of fossil fuels by a certain date?

That sort of group exists! It’s the global climate negotiations, formally known as the United Nations Framework Convention for Climate Change (UNFCCC) and I believe in the coming decades it will become the most important body in the world.

There’s a few important words I haven’t used to describe the UNFCCC or its actions, and that includes “government” or “orders” because the Convention doesn’t have any more power than its 198 member states decide to give it. If at any time a country doesn’t like what the Convention is up to, it can just stop doing it. Like when then-President Donald Trump decided to pull the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement, an important part of the Convention.

For big, developed countries like the U.S. there are no direct consequences of not complying with the Convention. But if the world is going to avoid the significant effects of climate change, countries will want to be part of the Convention and therefore comply with its agreements, and as the effects of climate change become clearer, those agreements are likely to become more wide ranging and impactful.

Since the Convention isn’t a government body, it has no ability to force anyone into compliance. Instead, it relies on global political pressure to encourage various states to act. But before I get into how that works, it’s important for Americans to consider that outside of their country, just about everyone except citizens of major oil producing states believes humans are responsible for climate change and that unless major action is taken, the world will suffer irreversible consequences to the environment, including major species die-offs, sea level rise, permanent climate shifts, and more.

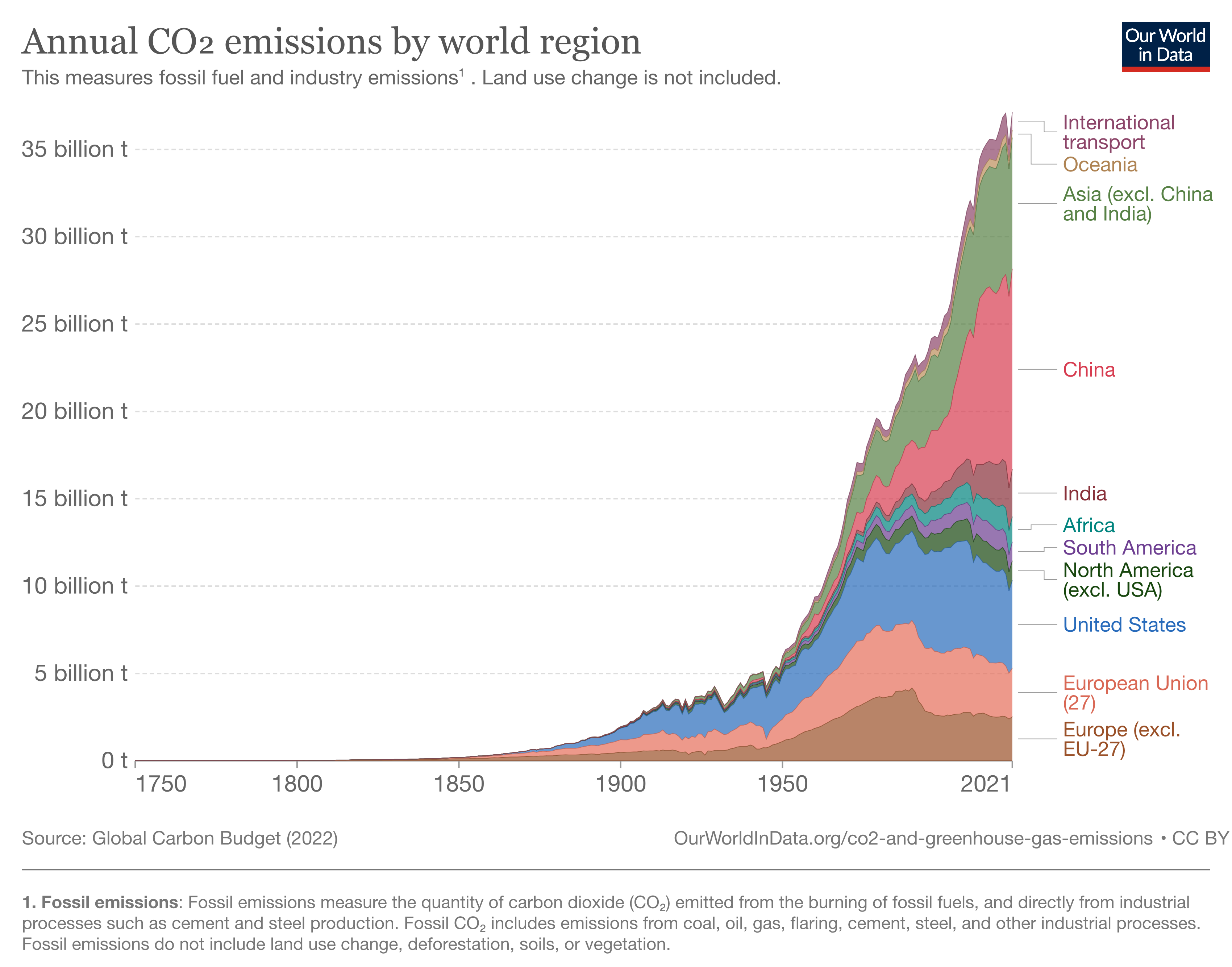

The major sticking point with climate negotiations is that the vast majority of the carbon emissions mucking up our climate come from the U.S., China, and India, equaling about 21% total global emissions. Similarly, a very small number of counties are exporting most of the fossil fuels that cause emissions, including OPEC nations, like Saudi Arabia, and other oil and coal producers like the U.S., Russia, and Australia.

Those few dozen countries are holding up decisions most of the 198 other parties to the Convention have generally agreed to. And because the Convention is not like a representative legislature, where everyone has to hew to the decisions of the majority, if the biggest polluters don’t want to make a change, then everyone else has to keep nudging them along until they do.

In some ways, the global climate negotiations are similar to a legislature where it has a set of founding documents. The UNFCCC was created in 1992, when the global community, excited by the success of the 1987 Montreal Protocol, which banned ozone-depleting chemicals like hydrochlorofluorocarbons, decided to tackle the threat of climate change. The exhilaration for stopping climate change in the early 1990’s was perhaps tempered by the sense that at that time, climate change still seemed like an outside possibility, rather than a certainty.

In the early years of the Convention, the main focus of annual meetings, called the Conference of the Parties, or COPs, were on the science of climate change. The Parties focused on how to measure the levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and what sort of changes we should anticipate if it increased. Fortunately, a scientific body to coordinate research, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, had been created in 1988, and this group led and answered the Convention’s scientific questions. Since its founding, the IPCC has been the unchallenged, unparalleled organization for global climate science, drawing upon experts from every country.

By 1995, it was becoming clear that carbon emissions were having an impact on our climate – although scientific reports lacked the “five-alarm fire” tone they have today. To set standards, the Convention agreed on the Kyoto Protocol, which directed member countries to decrease their carbon emissions against 1990 levels. In particular, it set limits for the 33 most developed countries at the time, known as “Annex I” (because the list was an addendum to the Framework Convention) parties. The Protocol called for the United States to reduce its emissions to 93% of 1990 levels by 2012.

And here is where the “voluntary” part comes in. While then-Vice President Al Gore signed the Kyoto Protocol for the U.S. in 1998, the treaty did not go before the Senate for ratification because big polluters like India and China were not Annex I parties, and thus did not have specific levels to adhere to. President George W. Bush withdrew from the Protocol in 2001, and the U.S. blew through its carbon emissions levels, only reaching 99.6% of 1990 levels by 2021. The U.S. remains the only major nation to not sign the Kyoto Protocol.

In 2015, at the 21st Conference of the Parties, or COP21 in Paris, optimism grew again, as parties signed the blockbuster Paris Agreement, which included numerous major agreements, including:

- Aims to limit global warming “well below” 2-degrees Centigrade and to pursue efforts to keep it below 1.5-degrees.

- For all parties to set national contributions to limiting climate change. Then-President Barack Obama pledged to cut emissions by 26% below 2005 levels by 2025.

- Every country shall make a national pledge every five years, and beginning in 2023, a “global stocktake” run by the U.N. will measure each country’s progress in reaching these goals.

- Developed countries “shall provide financial resources to assist developing countr[ies]”, although exactly how much, which countries, and under what circumstances was not determined.

- “Parties are encouraged to take action” to protect forests and other carbon sinks, although indirectly mentioned, the agreement clearly supports carbon credits or related financial vehicles.

President Obama signed the treaty and the U.S. Senate ratified it in September 2016 with China. Then, in June 2017, then-President Trump withdrew from the treaty. And finally, in January 2021, President Joe Biden rejoined the treaty.

There were no real financial consequences as the U.S. juked back and forth on the Paris Agreement, although plenty of countries criticized the U.S. – and the nation’s diplomatic status withered. And here is the real weakness of the climate treaties: If you choose to ignore the reality of climate change, then nothing really bad happens to the U.S. if it pulls out.

Still, I’m an optimist who chooses to believe that United States policy will continue to believe that climate change is a serious threat to the globe and that the country should do its best to oppose it. Right now China and India are doing the same thing, so it would appear that the world is moving towards making significant commitments towards fighting climate change.

And for the upcoming COP28 in Dubai this December, that includes a number of major issues, including:

- Setting a fossil fuel phase out schedule.

- Creating a debt relief program for developing countries wracked by climate change-related disasters

- Deciding whether the goal is to stay under 1.5-degrees, or 2-degrees of global warming. We’re currently at 1.1-degrees.

Also under discussion, but likely not to reach this year’s agenda:

- Creating global standards for carbon emissions credits, which for financial reasons is tantamount to creating a new global currency.

- Making payments to developing countries to assist with their conversion to a green economy, which U.N. and other estimates reach between US$1 and 3 trillion a year.

- Who qualifies as “developed countries”? Does Israel? Brazil? China? Developed countries will be on the hook to provide financial assistance to developing ones.

While everything under consideration at the Convention is through voluntary compliance, the issues at hand are weighty, expensive, and likely have the support of the vast majority of the world. For instance, the idea of creating debt relief for developing countries has 131 states in support, including China. Last June, the U.S. Secretary himself, Antonio Guterres, publicly asked when fossil fuels would be phased out.

While plenty of Americans want to “drill, baby, drill”, global pressure is demanding otherwise, and it’s becoming harder to ignore that pressure – along with all the heat, drought, and smoke we get in the summer. It might take a few years, but watch closely for the UNFCCC to become one of the most important political bodies in the world.

Other Things Happened

- 72% of GOP voters think the economy should be prioritized over climate, while most voters disapprove of Biden’s approach to climate change.

- The federal government is preparing to pay companies to remove carbon dioxide directly from the atmosphere.

- A U.N. committee on deep sea resources met for two weeks in Jamaica and couldn’t come to an agreement, but it seems that next year there might be a consensus on banning deep sea mining, despite Chinese opposition.

You made it to the bottom! Here’s 50 strange things you can get on Shein. Sign me up for the bread pillow.