Are electric vehicle sales topping out?

Sales of Battery Electric Vehicles have been so consistently up and to the right over the last few years, that climate boosters – and even car makers – have begun to take for granted the idea that everyone will soon be driving EVs. Incredibly, about 11% of all new car registrations around the world were BEVs in 2023, about 9.5 million cars.

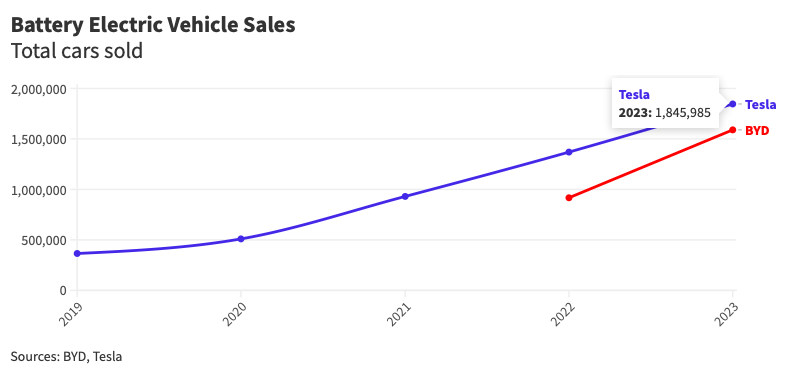

The world’s two biggest BEV auto manufacturers, BYD and Tesla also had record years, selling 1.6 million and 1.8 million BEVs respectively. In fact, Chinese manufacturer BYD temporarily passed US-based Tesla as the world’s biggest manufacturer in the fourth quarter of 2023, but then came crashing down in the first quarter of 2024, selling fewer cars than Tesla and fewer cars in the quarter than it had since early 2022.

And BYD’s poor BEV sales performance was matched by just about every other car maker in the world. Tesla’s sales dropped, and Ford’s electric vehicle sales slowed so much, it decided to cancel the roll out of two more BEV models.

Suddenly, it’s beginning to seem like, around the world, BEV sales aren’t always going to be up and to the right. It’s far too soon to make the call, but what if the surge of BEV sales over the last few years was driven by excited early adopters? What if we’re rolling into a “mushy middle” of customer demand, where buyers are price and feature-driven, like all traditional internal combustion engine car buyers?

The difficulty for auto manufacturers is that while you can decide to shut down production in a matter of months, ramping up production can take years. It’s not easy to tool up factories, build supply lines, and hire trained workers. So, whether this is short-term or permanent sales decline, is an important question to answer as soon as possible.

Bloomberg yesterday asked a similar, difficult question yesterday, why are three of the most technologically advanced countries, Japan, South Korea, and the United States, all have BEV sales rates below 5% total national sales? Globally, BEV sales were 11% of all new cars in 2023. The conclusion Bloomberg comes to: That each country has its own local peccadillos (infrastructure problems in Asia, range anxiety in the US), probably reveals the challenge ahead for getting the world to switch over to electric cars.

The world didn’t switch from using pack animals to cars overnight. Even large parts of Europe were using horse and cart transport in the 1960’s, and there are still large parts of the world that rely on animal transport. The switch took time not just because cars were more expensive than pack animals, it’s that cars required a whole new infrastructure – and plenty of people were comfortable with the old.

Electric vehicles require a similar sort of adjustment. Swapping out centralized gas stations for distributed chargers. Eliminating petrol delivery and building a more robust electricity delivery system. Dropping refineries for gasoline and constructing solar and wind power generation.

It’s all new – and none of that considers the automobile customer’s preference. What if the only time they can buy a pack of cigarettes – behind their spouse’s back – is when they buy their gasoline? What if setting up a charger in your home garage is too aggravating? These are real concerns I’ve heard from people I know.

So far, American, European, and Chinese governments have been relying on market incentives to increase auto sales. All three countries offer consumer tax incentives when you buy a BEV. And the US and China have also aggressively subsidized electric vehicle manufacturing. Through tax incentives in the US and Europe, as well as through government lending programs in China. The US has also created regulatory programs requiring auto manufacturers to aggressively market BEVs, to ensure total auto emissions decline over time.

But what if that’s not enough? What if consumers – not just in the US, but everywhere – decide they don’t really want to deal with the hassle of switching to electric? Then we’d have a whole new set of policy problems, and I wonder if governments – both Western and Chinese – would have the will to force consumers to ditch their gas cars for electric ones.

I think this is the real problem car manufacturers are worrying about after last quarter’s sales numbers.

Ideas

Chinese President Xi Jinping and US President Joe Biden spoke on the phone earlier this week and specifically discussed working together on climate. The two leaders seem to be seeking “win-win” agreements and as demonstrated with last year’s agreements at Sunnylands and COP28, there’s already progress on a new Sino-US accord on methane and coal use, which end up could drive COP29 this year. [Readouts from China and the US]

But all is not rosy with the US and China. China is very unhappy with US tariffs on solar and EV batteries, as Xi mentioned in the China readout of his call with China. China is taking the US to the WTO court to protest EV battery tariffs. Also, China’s lead climate negotiator staked out a position by stating (the obvious reality) that fossil fuels will have a place in China for some time.

For years developing countries have been calling for the US to invest real money in a grassroots green transition. This week the Biden Administration committed $20 billion to doing just that – but in the US only. As part of the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, the US Environmental Protection Agency will dole out grants to nonprofits in disadvantaged communities “to reduce climate and air pollution while also reducing energy costs, improving public health, and creating good-paying clean energy jobs.” Maybe if Biden’s reelected the next chunk of money will go to the UN’s Loss and Damage Fund?

Tuesday I wrote about how the differences between US and EU tariff policies on Chinese solar panels are leading to differing adoption rates. The Wall Street Journal has a more in depth look at how the same thing is happening with EV cars due to US tariffs and everyone else’s open markets. The result: Tesla is big in the US, but rapidly fading everywhere else.

Something I didn’t think of: Monday’s eclipse could cut US solar output by 40 GWh.

A US company is planning a 2,000 mile pipeline from Illinois to North Dakota to hoover up CO2 off gassed from 57 ethanol fermentation plants. The resulting project could result in sequestering tens of millions of tons of carbon a year. But, NIMBY safety panic, and tangled local permitting laws have slowed the project down to a crawl (two other similar US projects dropped out last year). Meanwhile, the UK is building a smaller, 90 kilometer CO2 pipeline in Northwest England that has barely registered a peep of concern.

Climate Change is a Death by 1,000 Cuts: Southern Africa drought, drought in Southeast Asia, India Summer heat wave, Tunisian goat herds depleting, record US home insurance premiums, record Chilean heat wave, lowering sperm count, Atlantic species invasion of Mediterranean, Spanish olives threatened, lowering coffee crop, thinner potato crop, cocoa crop crisis,

Climate Politics News

Ivory Coast bets on solar as part of renewables drive [Reuters]

A big week for climate policy in Australia: what happened and what to make of it [Guardian]

Shot: US Steel plant in Indiana to host a $150M carbon capture experiment [Canary Media]

Countershot: U.S. Steel Is Trying Carbon Capture. Experts Aren’t Impressed. [Heatmap]