“Trust is very low,” says Nepalese climate finance leader. “It's no longer a developing country issue.”

For a decade, Raju Pandit Chhetri has been a leading proponent for the Green Climate Fund, and thus, an expert on climate finance, the leading climate issue today. Chhetri is also the Executive Director of the Prakriti Resources Centre, an environmental justice NGO in Kathmandu, Nepal and a regular Nepali delegate at COP climate negotiations..

Last week he made time for Heat Rising to talk about the Nepalese initiative with other small mountainous countries to create a mountain country climate negotiating bloc, his expectations for where funding for climate finance would come from, and how small countries like his think about climate negotiations – when so much of the power lies in American, Chinese, Indian, and European hands.

[This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.]

Heat Rising: I want to ask you about the new Mountain Partnership that was formed at the last meeting at COP28. Do you see that as an important new tool, a positive development? And how do groups like that add to the influence of smaller countries like Nepal?

Chhetri: Yes, well, in the UNFCCC process, any interested countries can come together and form a group to push certain items or certain things in the process of climate change. The thing is, because Nepal is a mountainous country, for us, mountains are very key. I mean, it's not just Nepal, but the entire world.

What Nepal sees is that there is a huge linkage between mountains and the ocean, and the ocean biodiversity or ecology. In similar fashion, the mountain ecology is also equally important and is very fragile and that has to be taken care of, and you can see until before COP 28, there were no mentions of mountains at all.

That was the basic idea behind [creating] this Mountain Partnership. But, I have to be very frank, when you talk about mountains, it's a very tricky issue because, like, you know, your country, the United States, also has mountains, and Canada. You have the Andes, the Alps in Europe, or the Himalayas. We call that The Third Pole.

So, when you talk about the mountain agenda as such, what is it that we're trying to push? Because in the negotiation process, there’s always a divide between developed and developing countries. That's how the negotiation really takes place.

You'll have to differentiate two things here. When you talk about Mountain Partnership, a partnership as such is a different initiative with where developed and developing countries come together to tackle issues of mountains and to address mountain ecology, probably even channel resources and all. But when you talk about a negotiating bloc, like what you mentioned in the UNFCCC negotiations, that becomes a little political where you have to say who does how much of mitigation. So until now, there is no such strong negotiating bloc in the negotiations.

Heat Rising: Moving to a different topic, last week India announced plans to seek $1 trillion for the New Collective Quantified Goal, an effort to consolidate various climate finance projects. Considering the current circumstances for raising money for all these different things, is that a realistic number?

Chhetri: Yes. Well, and for this year, the NCQG, the New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance is going to be extremely important and there's already anticipation that this year's upcoming COP is going to be a finance COP. So the NCQG process in April and towards the end of April, they're already meeting for the first time in Columbia to discuss exactly these numbers and how to go forward at the end of this year.

So on that front, there are many numbers out there, whose number do you believe? Some say we need $5 trillion per year, some say $7 trillion, and we don't know the nitty-gritty. Africa Group a few years back said that we will need the scale of $5 to $7 trillion if you want to really address climate change and bring it to 1.5°C. So, those numbers are out there.

But the thing is now it's a political game. There's a lot of these numbers being thrown out, but we don't know the nature of them. So, when you heard about India proposing $1 trillion, I mean, it caught everybody's attention, right? In a similar fashion, there will be another group of countries saying that this is the number that we need. Somebody might say, "No, no, no, $1 trillion is only needed for the adaptation. We might need another trillion for just the, let's say, mitigation actions or loss and damage." Those numbers... are yet to be negotiated.

People, countries are taking this up, and the research has shown that if you want to really tackle climate change, the amount of resources that is needed is extremely high. But the nitty-gritty means that not all the money, the public money, will be coming from developed to developing countries. Probably that also means... how much of the share is something that the countries are already putting in? Because it's about accounting as well.

You will see now that a lot of the developing countries themselves are already doing a lot of climate action. They're not waiting for developed countries to give to them. We know that the developed countries have not even met the $100 billion goal for the Loss and Damage Fund.

You know, the current flow of finance is not adequate if we want to stay below 1.5°C, and that's not possible, and we already know, with all the Nationally Determined Contribution or country plans, even if they implement all the plans now, we're still in a 3°C world. Right?

What is key is how much of the resources is being thrown from developed to developing countries. How much of the resources developed countries are themselves putting into their own countries? How much of the resources are developing countries themselves contributing for their own adaptation and mitigation and access? I think if you put in all those in numbers, it's of course going to be a trillion

Heat Rising: Speaking of which, rich countries have been slow to make significant contributions. My own country, the United States, contributed $17.5 million to the Loss and Damage Fund. Is the problem that developing countries aren't making enough noise or is the problem internal politics of the rich countries?

Chhetri: What I see is an issue of trust. It's very low because we know that the developed countries were supposed to also do education and mitigation action, which they have not done. We know that even the bigger developing countries are out, based on their capacity, they are supposed to do much more.

The $100 billion goal was agreed to in 2009. Developed countries, you know, they had two processes. Then in 2009 in Copenhagen when they signed the Copenhagen Accord [summary], they said for three years, 2010, 11, and 12, they would give $10 billion per year for three years, and that money would scale up all the way to $100 billion by 2020, and that later on, we agreed in 2015 that it will be $100 billion

So, what that leads to is developed countries had almost about a decade to really prepare. But I think they were just not that serious in terms of really taking that into account and this is not my words but the developed countries themselves have clearly said in the negotiations that, “Yes, we have not acknowledged it.” They said that, “We didn't take it seriously. We did not meet the goal that we promised and it's been embedded in the Paris Agreement.” And one of the drivers of the [2015] Paris Agreement or implementing the Paris Agreement was that $100 billion goal as well.

So, I think when you see that from the perspective, it's also the internal politics of various developed countries. Like for instance, the US, you know, they promised $3 billion when Obama was there for the Green Climate Fund [at COP15 in 2009]. [The US has] only delivered $2 billion up to now. While others, like Europe and other countries have already done it three times. Now we're just running the third replenishment, second replenishment process from the initial one.

That is when you realize, for the Loss and Damage Fund, it’s $17.5 million? It's like a peanut. It's like, I don't know, why did they even do that? It would have been better not doing it other than putting that [low amount of] money, you know?

You don't see much seriousness also from [developed] countries, probably that is the reason why trust is very low. and having said that, the impacts of climate change are already there. It's no longer a developing country issue. U.S. forest fires, in Australia, in Europe. The floodings. It's everywhere now.

Which means that if we don't take it seriously in terms of implementation, then we are, I think, in serious trouble.

Heat Rising: So, thinking about that, do you see that maybe there's a potential funding source through a global tax, like on marine fuel, or taxing airline travel? Is that the solution, finding some separate revenue source that's outside of a budgetary commitment?

Chhetri: Definitely. A country like ours has always been open to innovative sources of financing. We know that a trillion dollars is not going to come from the budget of the developed countries to developing countries. When $100 billion is not being met, a trillion dollars is a different level of mobilization, right? But it's not that in the world there's no money. There are resources. But how do you mobilize the resources?

You mentioned whether you bring in the bunker fuels with the aviation and the shipping industries, or you do other taxations on how ever the money flows all around the world, or you try and do some kind of innovative economic taxation. Let's say the fossil fuel industry, for instance, rather than levying them or taxing them – they have been provided subsidies.

Heat Rising: Have COP meetings basically become a struggle between the biggest carbon emitters? What role can developing countries play and how do you set expectations for negotiations? Knowing that you're basically going into a room full of elephants?

Chhetri: Well, I mean, for a country like ours, Nepal, they always say this: If not COPs, then where is the forum for our voices to be heard? There's none. You know, G-20, we don't even exist for them. And with their other various forums, where it's very small, we don't even exist for them.

That is the reason why for a country like Nepal, COPs are extremely important, regardless of what outcome takes place. For us to voice our concern, to tell the world the problems that we are facing, I mean, I'm just giving an example of Nepal.

This is the same case for many of the developing countries, like in Bangladesh, in Ireland, or Bhutan, or like, you know, many of the African countries. This is the only forum where you can voice our concern first. Second, we have to be able to voice our concerns. These COPs have been really putting many countries on the spot to say what they are doing in terms of climate action. Even if it's a very marginal step, then it gives a signal.

For instance, from the last COP, it says now it's time for us to move away from fossil fuel, right? So, you know, transition away from fossil fuels. It's a signal to the world that the way we are moving now is not helping any of the countries of the world.

But again, this is the political process. Sometimes the ring of powerful countries, [versus] a country like ours, or at least developed countries, you know, we suffer. But that political bickering is not impacting climate on the ground.

We continue to face that in Nepal now...We had a long winter drought. We had several forest fires. There have been many people killed, houses burned, and so on and so forth. This is happening all across South Asia, and I was just told here that it's happening in Latin America as well. So, you know, these kinds of problems are just because the bigger guys are continuing to fight the process.

Climate change is not stopping, and the impacts are happening, and that's the only forum for us to [talk] to the media, to the world, to say that, you know, these are the problems that we need to address. We believe that if we don't keep trust in this process, then again, where do we put this? There's no other forum for us to voice our concern.

Heat Rising: [Barbados Prime Minister and climate finance leader] Mia Motley recently called for multiple climate finance meetings every year. She said, you could do it three or four times a year. Does that make sense to you? And if you were to have multiple meetings, what do you think would be discussed?

Chhetri: Yeah, so there's been two sides of the debate here. There are countries who have been saying that we need to have a high level meeting frequently and then really push our politicians. So that they can grasp that and not make it political, but to look from the people's perspective and environmental perspective. But there are also countries who said, now the COPs are happening every year, it's too expensive, let's do it every once in two years. That proposal is on the table. It's a two-sided thing. But I think it's a bit early to not have it every year. So, that's what I would say.

Just having too many meetings doesn't mean that action will be taken. Getting that political awareness and commitment and trying to hold the politicians to account, to make them morally responsible to what they commit and then really implement is the key factor.

We can say, "Okay, at this COP, this is what you said, But have you done it or not?" Now, when you look at the Global Stocktake last year, we are behind in ambition in mitigation targets, we are behind in adaptation actions, we are behind in finance, everything. So, we are again in a 3°C world.

In order to close that gap, COPs are the only inclusive forums where all the countries can commit and then really say who is doing what and how much, and they can be assessed. Also, there's nothing like legally bringing them to account, at least morally you can hold them to account. That's only the forum.

Like what you see? Please forward to a colleague.

Ideas

John Podesta is the US’ new lead climate negotiator and so far he’s shying away from taking any specific negotiating positions. For now he’s calling for China to reduce its coal use and calling climate finance a top priority. Podesta has a tough job as negotiator, since COP29 will be held after the US’ Nov. 5 elections. If Trump wins, Podesta will have no credibility in Baku. If Biden wins, Podesta will not have had time to secure US political support for commitments other countries will be calling for at the expected “climate finance summit”, as people have been calling COP29. This year, the US team will have little negotiating leverage.

All 26 members of the Loss and Damage Fund Board have been nominated. 12 from developed countries, and 14 from developing countries. The Board has a long list of decisions ahead, including creating a system for how to request grant funds, under what circumstances, and which countries would get priority for the $100 billion a year the Fund hopes to receive. No meeting date has been set yet.

Chinese solar panel makers will produce 2x the global demand for their products in 2024, a BloombergNEF study shows, and will increase to 3x in 2025. This suggests that panel prices will drop through the floor, import tariffs won’t be able to keep up, and non-Chinese manufacturers will likely be gutted by overseas competition. China’s growing deflation means the country desperately needs exports to succeed. The US and Europe will have to make a choice: Defend their local production for the sake of local jobs, or ride the wave and start putting up cheap solar everywhere, which will likely revolutionize the power industry.

The legitimacy of voluntary carbon market credits continues to take a drubbing. One forest preservation project in Zimbabwe saw 86% of the proceeds go to fees, with only 14% of €100 million going to actual preservation. Meanwhile, in anticipation of higher standards for carbon credits from the UNFCCC’s Article 6.4 negotiations due at COP29, many voluntary credits are undergoing an audit. One study found only 6.4% of reviewed credits meet a high standard of ethics, sustainability, and transparency. With all that junk on the market, two questions remain: Who paid for all the junk? And, who was purposely ignoring the problems?

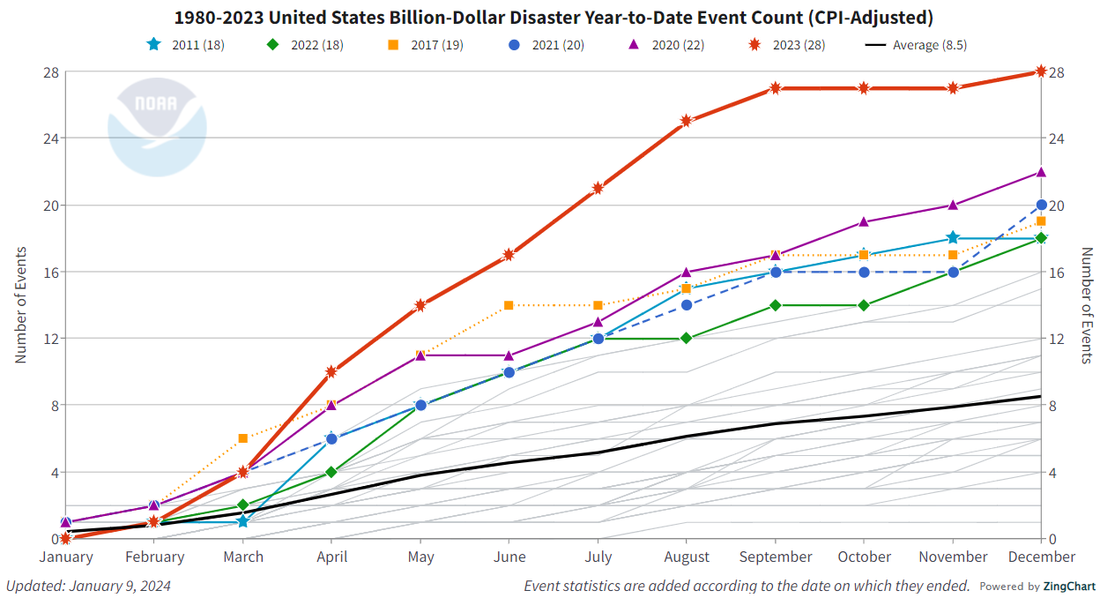

The US climate.gov website (which is very good!) has a data-rich blog post on the increasing number and size of natural disasters in the United States (see chart below). “In 2023, the U.S. experienced 28 separate weather and climate disasters costing at least 1 billion dollars. That number puts 2023 into first place for the highest number of billion-dollar disasters in a calendar year.” More evidence that the most likely driver of developed country attention to climate change will be insurance costs.

Climate Politics News

Oil’s endgame could be highly disruptive [Economist]

It’s never been cheaper to buy an EV. Here’s why. [Washington Post]

The problem of equity in IPCC reports [The Hindu]

COP29 host Azerbaijan plans to upgrade climate target [Reuters]