The problem with confidence and solving climate change

For any new skill or project, the beginner launches in, brimming with confidence. But inevitably, they discover that really, they don’t know anything.

It’s a fact of human innocence, that when we encounter new problems, our natural impulse is to just think, “Hey, I think I can fix that!”

This is not necessarily a bad thing. It means we humans dive into problems, and often fix them, if they aren’t too difficult. But when they are difficult, the human problem solving impulse (also known as “confidence”) keeps us moving forward as we try to untangle one knot after another. If the problem is unexpectedly complicated, our confidence gets worn down bit by bit, until we either give up, or dedicate ourselves to learn more so we can solve more complicated problems down the road.

The first group of people, who give up and move on, are called “normal people”. Those in the second group are called “experts” by the normals, but the experts refer to each other as “suffering idiots”.

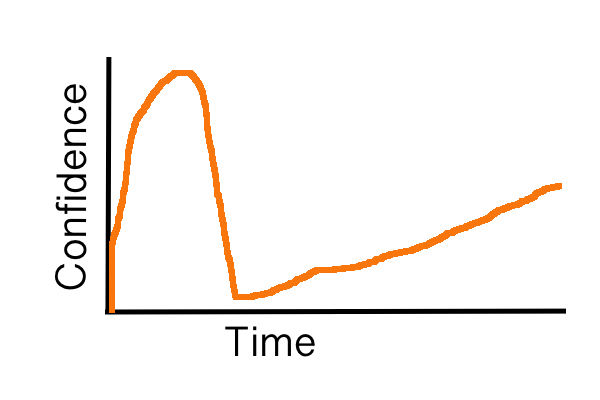

And this is a great time to share one of my favorite graphs.

For any new skill or project, the beginner launches in, brimming with confidence. But inevitably, they discover that really, they don’t know anything, and maybe they should get their nose to the grindstone. Only later, over time, does the person gain confidence, but never to the level of a beginner. True experts remain humbled – but gain confidence as they learn the complexity of what they do.

This graph has been on my mind as I’ve started up Heat Rising. This is my ten-billionth newsletter/blog project, so I don’t feel like a beginner for that. I have very low and slow expectations for a newsletter – I imagine it’ll take years before I see any real growth here. In contrast, I’m mostly a climate beginner. Although I once worked heavily on the topic, that’s two decades past. I’ve been cautioning myself to remember that this climate and green tech stuff is hard, and slow to show results.

That’s something many, many friends counseled me on too. “Climate’s kind of a bummer.” “This is virtually unsolvable, why spend your time on it?”

The massiveness of everything related to climate change easily washes over us. When considering how complex the problem is, with references to chemistry, acronyms for multinational bureaucracies, politics, and more, “The world is screwed and there’s nothing I can do about it,” quickly becomes our default state. There’s so much to worry about, it’s so hard to understand, and there are so few ways one person can directly affect change, that we just decide to live with it all. The world is warming up. So what? I’ve got bills to worry about today.

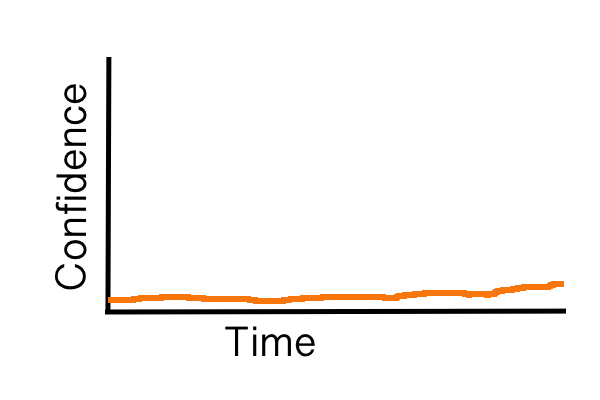

And so, for climate, I think a different graph applies.

For most of us, there’s almost no confidence in the process from the very beginning. Except for people with white knight syndrome, a love of science, or an undaunted desire to make the world a better place, the energy to fix climate change is sapped out from the very beginning.

Each day, there are a thousand things we do that are contrary to the steps needed to combat climate change. I heat my house with natural gas, drive my internal combustion engine car to the grocery store, eat a fried chicken sandwich with imported tomatoes, and fertilize my lawn. That’s not even the bad stuff! I fly on airplanes a few times a year and eat lots of beef. One carbon footprint calculator estimates that I’m spewing over 20 tons of carbon into the air every year.

I’m embarrassed to say that because of all my travel, my footprint is higher than most Americans, which is around 14 tons. An average Frenchman? Around 5 tons. Sacré bleu!

I’d love to get an electric car. But they’re pricey, the ranges are too low for what we need, and there just aren’t enough chargers between here and Lexington, Kentucky, where my mother-in-law lives. We’ve thought about getting solar panels, but that’s probably a $15,000 up front investment, money we need to spend elsewhere for a college-bound teen. My wife works for Amtrak, so I can take the train for free sometimes – I’ve already gone to Milwaukee, New Orleans, Boston, and New York that way. It’s fun, but slower.

All this is to say that: Yes, we can individually make changes that have an impact, but real change won’t come unless it’s systemic. We need cheaper electric cars with longer ranges. Less expensive solar installations. More frequent and faster long-range trains. Less beef and more Impossible Burgers (which are delicious).

The trouble with systemic changes is that entire systems need to get behind making the change, and then sustaining that change. This gets even harder when the system is basically every American with a car. Or people growing food globally, or beef-eating everyone (Hindus have a great head start here).

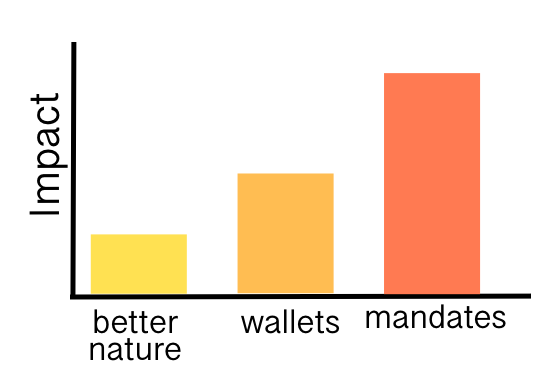

When you’re trying to make systemic change, there’s really just three approaches you can take:

- Implore to people’s better nature;

- Appeal to wallets; or

- Mandate the change through force or government or arms.

Number one works well in societies with a broad sense of common good. That’s what you’re seeing happen in Northern Europe with all those Scandinavian and Scottish renewable energy projects (please ignore all the North Sea oil, though!).

Number two works well in societies with well developed markets and when green tech can provide a convenient solution that doesn’t cost too much. See the increase in EV and heat pump sales in the United States as potent examples here.

Number three works just about everywhere – to an extent. You’ll always end up with outliers who fight the system for their reasons, and if the population doesn’t believe their sacrifices are worthwhile, they’ll inevitably resist to a point where force is inadequate. Look no further than the U.S. and Southern European immigration crises for an example of how little impact government force can have on determined populations.

For decades Americans have been trying method #1. That’s gotten us only so far.

While we’ve been nibbling on the edges of method #2, the U.S. finally made the plunge with the many tax credits and grants established by the Inflation Reduction Act. Inevitably, it seems, we’ll have to move to method #3. The question is will that happen because Americans as a whole want regulation, or because the global climate problem is so bad that our hand is forced? Either way, the American history of dealing with gun violence and immigration is not a good indication of how well we’ll manage the next step.

The trouble with moving up the chain of approaches – better nature to wallets to mandates – is that to successfully get a population to get on board, you require a higher level of confidence. People aren’t going to use tax credits unless they think there’s a technology they can use to make money. And thus, people aren’t going to follow mandates unless there’s a workable green tech solution they can follow.

In the end, our ability to successfully solve climate change is a function of public confidence that the problem can be solved – which is exactly why I decided to start this newsletter. I have the soul of the activist in me that wants to spread the word about how we can solve this and actually save our planet. America, and the world, needs to manufacture now just climate solutions, but a sense of common good – we’re all in this together and it needs to be solved now – before we can affect real change.

So while solving climate change is a technology problem, it’s also a public confidence problem, and I’m hoping this newsletter can be part of that solution.