Technology won’t solve our weak societal interest in climate change

Good afternoon!

So I’m working on something cool, which means I need more time to focus on it, which means I’m going to have to scale back this newsletter to twice a week, Wednesday and Friday. I’m pretty sure you can handle it.

But the cool thing I’m working on is a project to create a news organization that covers global climate negotiations! Yes, there are places that cover this, but not in the detail I think the process needs, considering it could set the rules for ending the fossil economy and how we’ll distribute trillions of dollars of climate aid to developing countries.

It’s a huge project, and it’s not like I’m heading off to start covering it tomorrow. In fact, I’m planning to do this as a non-profit that provides free reporting, so I need to get a lot of donor support before I can start up. Right now I’m spending my free time identifying potential donors and foundations, and then asking them if they’ll talk to me, someone they’ve likely never heard of before.

That takes some time.

Want to know more? I’ve put together a deck about it that you can download here.

Drop me a line too, if you have any thoughts on people I should be talking to. I always need good ideas.

See you next Wednesday.

-Mike

Most of the discussion surrounding climate change mitigation is about technologies we can deploy to reduce carbon emissions while ensuring our lifestyle doesn’t measurably change.

This strategy is deeply embedded in the Biden Administration’s response to climate: Tax credits to produce hydrogen so trucks, planes, and steel factories can go at full blast. Tax credits for EV cars and school buses so we can keep rolling on the highways we love so much. Tax credits for wind and solar power production so we can power all the factories, electric vehicles, and air conditioning we need to keep everything the same. And the biggest technological intervention of them all: Building tens of thousands of machines that will suck carbon out of the air and pump it underground.

The trouble is, technological intervention can only get you so far, and until we have a fully carbon-free energy economy, all of those actions will produce some amount of carbon, just considerably less.

An alternative line of thinking is to consider how to reduce carbon emissions in the first place. It turns out, most of what we need to do this already exists: Use mass transit, take trains, ride bikes, encourage higher density construction, use air conditioning and heating less, use less water with fewer lawns, pools, and more efficient appliances.

The choice to conserve also creates beneficial side effects of saving money and doing less damage to the environment. But the problem with conservation is that it constricts your actions somewhat: You can’t drive a nice, warm car with a radio to the store to get milk, you need to ride a bike. You can’t build a big, sprawling home in a pretty field far from others, you need to live in an adjoining duplex, or apartment among hundreds or thousands of other people you don’t know.

These two choices are clearly laid out in Charles C. Mann’s 2018 book, The Wizard and the Prophet, which discusses two differing approaches to environmentalism. Wizards want to use technology to solve environmental problems, while prophets encourage us to reduce our impact by using, and doing less.

The reality of our world is that no society does just one or the other, they tend to employ some balance of the two. In the United States, we certainly lean towards Wizardry with our EV technology and other gizmos, but we also have a bit of the Prophet with things like CAFE standards for auto emissions, increased use of denser zoning, and rules that require LED light bulbs instead of incandescent ones.

But some other industrialized societies, like in Europe and Japan, actually lean towards the Prophet with strict zoning requirements so that city and rural boundaries are much clearer. Or by building high speed rail systems so you don’t need a car or plane to travel to different cities. Or by encouraging safe bicycle travel in dense cities so you don’t need a car to get around town at all. Or by air drying clothes rather than owning a dryer.

A few American cities do this, but a trip to East Asia or Europe can be eye opening for many Americans, who discover that mass transit, density, and energy conservation can be a viable option that provides a great standard of living – sometimes even better than in the U.S.

Ultimately though, I think the American tendency towards technological solutions is because we have embedded in our political psyche an unwillingness to require sacrifice for the greater good. Our nation was built on the idea that if you don’t like what’s going on in your area, just move. Settlers moved west when they wanted to get away from city rules, and today plenty of Northerners move to the Sunbelt because they want warm air and less government interference in the form of taxes and regulations.

Whatever the reason, taking action of any kind to curb climate change has become a political issue in the United States and Europe. The New York Times’ Paul Krugman writes this week that “climate denial has..become a front in the culture wars” leading Americans to not only refuse to take steps toward climate change mitigation, but to deny that it’s a concern in the first place. Meanwhile, Reuters reports that Europe is beginning to experience a “greenlash” against mitigating climate change as well.

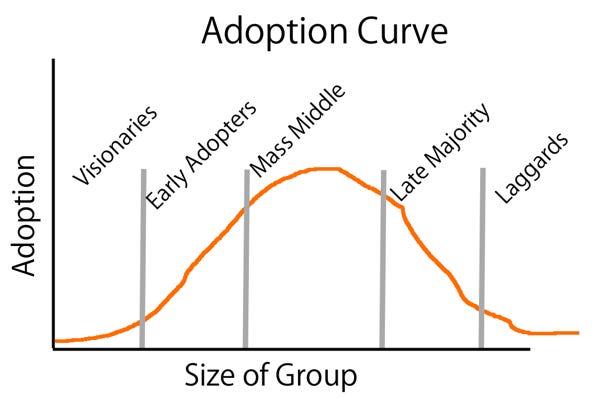

All of this seems familiar, right? We experienced a backlash against civil rights, women’s equity, seat belt laws, the internet, and on and on. Change is hard, and societal change rarely comes in one single movement: There’s the visionaries, then the early adopters, then the mass middle, and finally the foot draggers. The visionaries have been talking about climate change for decades now, and only recently have the early adopters really gotten on board.

Because humans are incredibly predictable, technology adoption follows the same curve, which in terms of size of the groups is essentially a bell curve (see image below).

Technologists also worry about another curve, the so-called “valley of death” where after a brief period of flurry of people picking up your technology, there’s a stall between the visionaries and the early adopters where little happens. Some technologies die in the valley of death, because they run out of money to support their development, but most others have some lean period where they keep promoting their tech, waiting for it to catch on with the masses.

Axios reported earlier this week that auto companies are trimming back their EV sales expectations because they believe “the next wave of consumers — the more price-sensitive "early majority" — is proving to be more elusive. It may be that EV sales are an indicator of societal interest in solving climate change: EV car sales go up, maybe so does interest in climate change?

Of course, all of this focuses on America’s obsession with technological (and market-driven) solutions for climate change. We’re not talking about people picking up bikes to pollute less, or taking the train, or buying an apartment in the city rather than a subdivision house to lower carbon emissions. For instance, a few years ago Europe experienced a wave of “green shaming” as short airplane hops were shunned in favor of rail travel. That’s still going on, especially in France, which banned all short-haul flights that couldn’t be served by a rail ride of less than 2.5 hours.

Can you imagine how that would go down in the U.S.? Even if we had such a rail alternative?

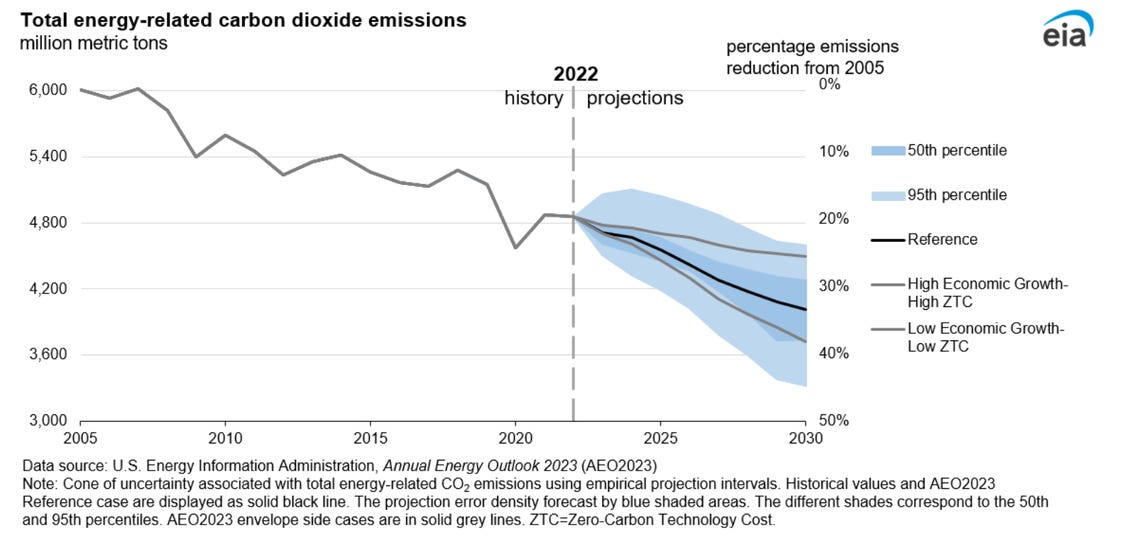

Earlier this year the Energy Information Administration, which is the federal government’s independent energy analysis office, released a report that, among other things, does not show that even our government thinks we’re going to hit the carbon emissions targets we need to reach. (see chart below) For reference, we need to be hitting less than 50% of 2005’s emissions by 2030 if we’re going to keep the earth from warming up more than it already has. And then we need to cut it to close to zero by 2040 if we’re going to be successful.

Ultimately, I believe our biggest problems with climate have less to do with technology and more to do with convincing society that we need to do this. Exactly how, I’m not really sure. But when I look to the last two great challenges America overcame, the Second World War and the Cold War, in both cases our government and society spent an enormous amount of energy into convincing us that the threat was real. You could call that propaganda, but you could also call it rallying the nation.

It’s time to rally the nation.

Other Things Happened

- The Biden Administration is proposing to move transmission line permitting from an independent board to the Department of Energy, which could radically speed up the process.

- Meanwhile, in order to kickstart the industry, the Department of Energy announced plans to buy $1.2 billion of carbon capture from nascent companies.

You made it to the bottom! True story: A snake fell from the sky and attacked a woman. Then it got worse. See you next Wednesday.

Thank you for reading Heat Rising. This post is public so feel free to share it.