Peak Fossil Fuel and the 90's lesson of Peak Oil

Good Afternoon,

If you’re a normal human, you may not have heard, but the energy industry was roiled this week when a top European government energy analyst predicted that we’ll top out on fossil fuel use in 2030. Previous experience makes me dubious. And I brought graphs.

-Mike

Fatih Birol at the 2022 World Economic Forum. (WEF / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)Back when I worked in the U.S. Department of Energy in the late 1990’s there was a great deal of talk about “peak oil”, that at some point in the maybe near future, the world would run out of oil sources. Depending on whom you talked to, peak oil would come at the start of the new millennium, in fifteen years, or maybe by 2030. Those of us who leaned green were excited by the prospect of peak oil, because everyone knew energy demand would only increase, but if oil resources were depleted, that meant fuel prices would go up and the world’s consumers would be forced to buy more efficient, less dirty cars and fewer greenhouse gasses would go in the atmosphere.

The free market’s invisible hand would take care of all our environmental problems! Hurray for Adam Smith!

But it didn’t actually work out that way because of fracking.

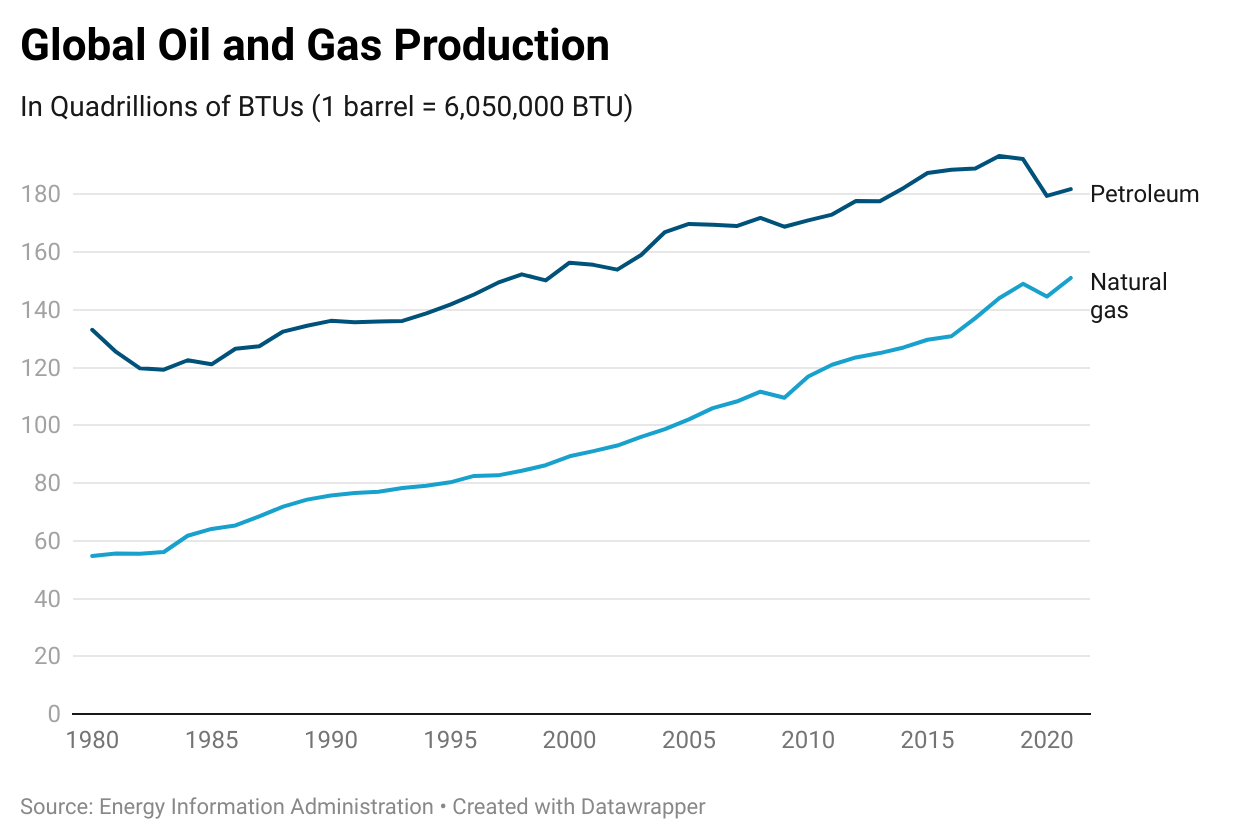

Faced with wells that were drying up, oil companies started pumping liquid slurries deep underground into oil shale and other previously undrillable gas and oil fields. The slurry added new pressure to porous rock formations, forcing oil and gas out the drilling holes. All of a sudden, withering oil fields in North Dakota and the North Sea and gas fields in Pennsylvania and Tunisia were pouring out fossil fuels, driving prices down and bringing a bonanza of fossil fuels. All of a sudden, oil and natural gas production were going up, only stopping to take a breather during COVID.

Now, nobody talks about peak oil any more because so long as there’s fracking, there’s plenty of oil and gas.

But look out for the trendy, new “peak fossil fuel” term getting tossed about. This one is coming from no less than the International Energy Agency (IEA), Europe’s quasi-governmental energy analysis agency. According to the IEA executive director, Fatih Birol, the Agency’s upcoming annual World Energy Outlook will project a peak demand for fossil fuels in 2030, “driven by the spectacular growth of clean energy technologies such as solar panels and electric vehicles”.

In a Financial Times editorial this week Briol is careful to note that the declines are nowhere near to limiting global warming to 1.5C, and “there can still be spikes, dips and plateaus on the way down.”

Not surprisingly, OPEC quickly rebutted the editorial, claiming that their projections see no decline of the kind. "Such narratives only set the global energy system up to fail spectacularly," said OPEC Secretary General Haitham Al Ghais.

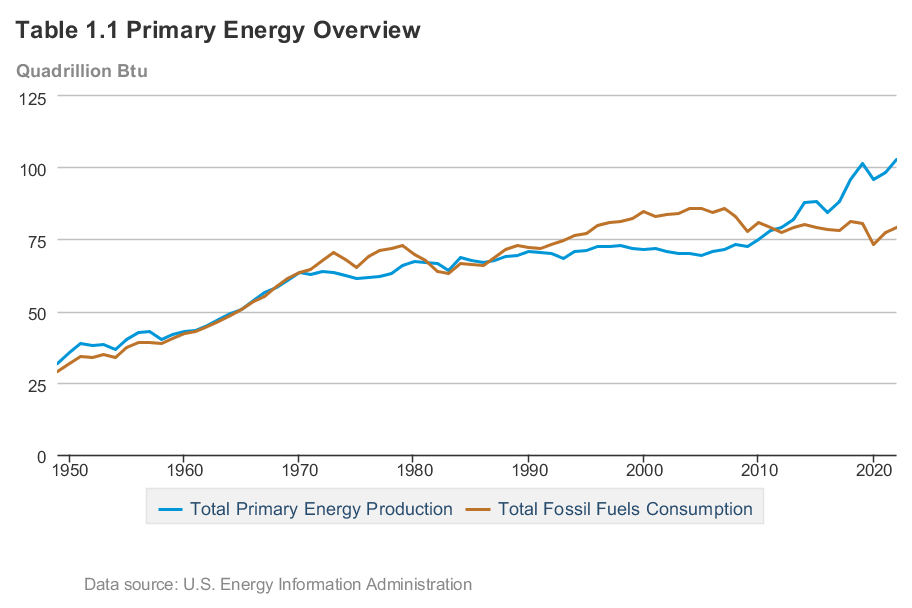

For context, consider two facts: According to data from the Energy Information Administration, the U.S. version of the IEA, actual U.S. fossil fuel use peaked in 2007. But, overall energy use as a percentage of overall consumption has been increasing, encouraging fossil fuel production to stay at a relatively steady level.

Although wind, solar, and other renewable energy sources are now cheaper than most fossil sources, green energy is working against a market already geared towards fossil fuels. For instance, consider the number of places you can gas up your car versus charge your EV on a long drive. Or, the fact that there’s already plenty of legacy coal plants ready to operate while solar farms need to be built and then found a place to connect to the grid – when interconnection is not so easy.

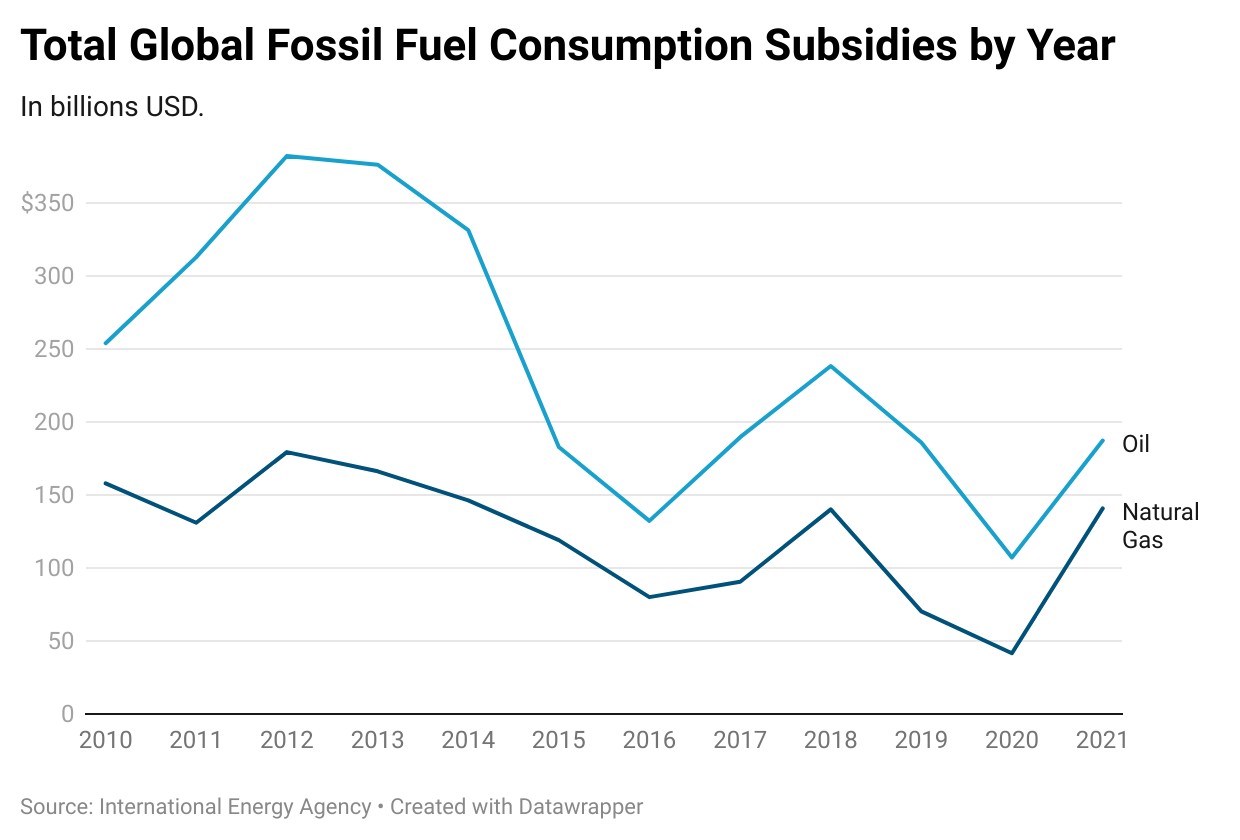

Let’s also consider how fossil fuels got so cheap: Since the Second World War, western governments have set up a number of subsidies for oil production. In the U.S., federal land lease prices for oil and gas production have been artificially depressed. In the U.K. North Sea oil production taxes are exceptionally low. But the granddaddy of all oil subsidies are the billions spent by Western countries to stabilize Gulf countries with U.S. and European military presences and military aid. Together this adds up to hundreds of billions of subsidies to global fossil fuel markets.

The reality of market frictions also make the switch from fossil to green so expensive. For now, it remains cheaper to pull oil out of the ground, refine it, and ship it on a tanker around the world, than it does to build a new solar farm.

Today, just about every major energy economy change has come as a result of some government putting its thumb on the scale. The Chinese gave huge, cheap loans to electric car companies like BYD and BAIC. Now, one third of all cars sold in China are EVs. In the U.S., the Inflation Reduction Act is spurring on EV production, heat pump sales, new hydrogen plants, and even carbon capture.

Regardless of your politics, putting thumbs on economic scales is what government does. Pro-defense conservatives want governments to spend on building up military production, pro-business types want wider roads, greens want cheaper EVs and nationwide charger networks.

If the 1990’s taught us anything about energy markets, it’s that energy use and government policy are directly connected. We should not expect green energy use to substantially increase without specific government policies, just as fossil fuel use will not decrease without a reduction in subsidies. That’s a fact oil companies are well aware of, and they are actively working to ensure their subsidies stay in place.

Other Things Happened

- Apple says its new watch is carbon neutral. But the real story is how Apple is flexing its supply chain dominance to actually go green.

- Developing countries are supposed to contribute USD 100 billion a year to assist developing countries to go green. The U.S. is only doing about one fifth of its pledge

Welcome to the bottom! Here is your digital reward, my favorite new, dumb instagram channel.

Thank you for reading Heat Rising. This post is public so feel free to share it.