How this year’s global climate negotiations are shaping up

Good afternoon!

I’ve been thinking a great deal about the upcoming global climate negotiations meeting in Dubai this winter. So, today I put together a summary of reports and missives I’ve seen so far from negotiators. Looking at what’s coming down the pike it’s easy to be discouraged, but almost all the major breakthroughs, like the Paris Agreement and last year’s Loss and Damage fund promise all came at the last minute. You never know what will happen.

-Mike

An overview of how global climate negotiations are shaping up

Sprinkled around the world are raging climate deniers like Rep. Scott Perry of Pennsylvania, who told U.S. Climate Envoy John Kerry in a Congressional hearing last week that climate scientists are, “grifters, like you are, sir.”

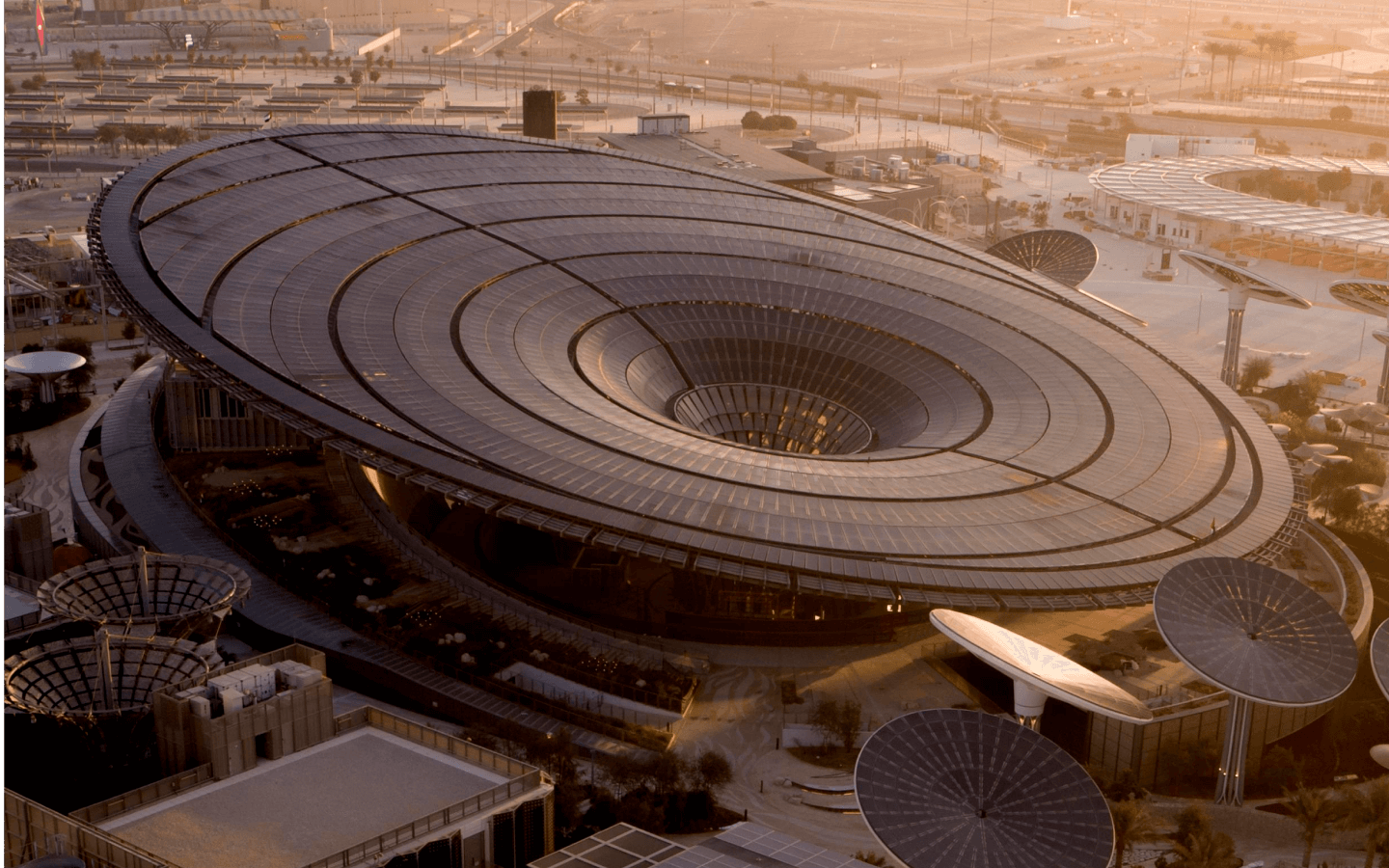

As global climate negotiators prepare to meet for the two weeks of the 28th Conference of the Parties (COP28) in Doha, United Arab Emirates (U.A.E.) starting November 30, progress will be delayed not by the ingrates of the anti-climate brigade like Rep. Perry, but instead by much craftier types. This last week negotiators began to assess the negotiations potential as the EU released its goals for the meeting, the U.S. and China climate envoys held a pre-meeting, and the COP28 President, Sheik Sultan Ahmed Al Jabar released an official agenda and goals for the meeting.

Already, five main issues are shaping up to take center stage in Dubai. Here’s a brief rundown of what negotiators will have to tackle this winter:

1. Results of the first Global Stocktake Report

Agreed upon at COP21 in 2015 as part of the Paris Agreement, every five years starting in 2023 the Global Stocktake provides a report card on the progress of each nation’s climate action plans. COP28 will deliver those reports and likely a tremendous amount of positioning as the biggest polluters, like the U.S., China, Russia, and India try to explain why they haven’t hit their promised targets. This will also be where the global community will unload the most invective on big polluters demanding them to take more concrete action over the next five years.

2. Funding Loss And Damage

Last year’s COP27 meeting experienced a breakthrough when rich nations unexpectedly agreed to the creation of a “Loss and Damage” fund to pay developing nations struggling with climate-related disasters. One way to look at Loss and Damage is like a global climate Marshall Fund, where developing countries are financed to retool their countries in the wake of rising sea levels, debilitating drought, or massive floods. But while the concept sounds great, the devil is in the details, as exactly who will pay, how much, under what circumstances, and which organization will manage the financing are all still undetermined. Meanwhile, constituents of rich nations are not too keen on the anticipated payouts.

3. Developing country financing for green technology

In 2009, rich countries promised to provide US$100 billion dollars a year starting in 2020 to assist developing countries to transition to the green economy. But, the first payment didn’t come until 2022, and even then it was for just US$83 billion, and it was mostly loans, rather than direct payments. Since then, one U.N. study has suggested it would take US$1 trillion a year to adequately transition to green tech and a recent Bloomberg study suggested over US$6 trillion a year would be needed.

On top of that, developing nations are using this moment to point out that their current state of debt is crushing their ability to grow. A proposal led by Barbados and endorsed by 130 countries including China, called the Bridgetown Initiative, calls for an end to the “climate debt trap” where developing countries experience climate disasters, obtain more debt to finance repairs, and then are crippled by new disasters before they are able to pay off the original debt. A meeting in Paris last month gave a lot of attention to Bridgetown making it a likely centerpiece of discussion in Dubai this winter.

No matter how you get down to it, it looks like rich nations will be required to spend a lot of money in developing countries to ensure a speedy transition to the green economy. The core questions have become: Who qualifies as a rich country now, and how much will each country be required to pony up?

4. The role of Carbon Capture and Sequestration (CCS)

The idea of CCS is this: You run big fans to suck carbon-dioxide out of the air. Then, either you then blow that CO2 down a deep hole, usually an old oil or gas well, and “sequester” it for thousands or millions of years. Another method is to chemically break the carbon out of CO2 and then bond that carbon with something else, like magnesium to make big blocks you can shove into old coal mines, or into cement to make “green” concrete. The thing is, these technologies are still very much in the demonstration stages and to adequately suck enough carbon out of the air, we’d need tens of thousands of CCS facilities running for dozens of years – about as many oil wells as we have running today.

Still, in almost all the models keeping the world from warming too much – warming more than 1.5-degrees Centigrade (we’re at 1.1C now) – count on CCS to some extent. Some countries with a big carbon problem (like the U.S.) or that produce a ton of oil (like the U.A.E.) really like the idea of CCS because theoretically, you could ramp up CCS operations so that you’re extracting as much carbon out of the air as all the fossil fuels are putting in.

Nobody knows yet if we can really scale up CCS, so it might be a kind of pipe dream. Nonetheless, how much the world will depend on and fund CCS is likely to be a big part of COP28 discussions.

5. Setting a phase-out date for fossil fuels

Today there are virtually no climate negotiators who deny that fossil fuels are the main source of greenhouse gasses. Even the U.A.E., the COP28 hosts, now admits there must be some sort of “phase-down” of fossil fuel use. But terms “phase-down” versus “phase-out” contain a key difference, as big polluters and oil producer nations want to keep using fossil fuels for as long as possible since transitioning to green energy is considered expensive and oil wells are a money spigot. Phase-down-ers suggest we could keep using fossil fuels through 2050, since it will take too long to fully deploy renewables, and CCS could cover the extra emissions for a while. Phase-out-ers point out that climate studies show that if we don’t quickly cut all emissions, say by 2035, we’ll blow past the 1.5C goal and commit the world to irreparable climate damage.

Ultimately, this question is about how much the rich world, China, and India are willing to pay to speed themselves and the rest of the world towards a green economy. And in order to make it happen, either the U.S., China, or India will need to unilaterally move towards a green economy to embarrass the others into taking similar action.

Other Things Happened

- It turns out that all the organic detritus piling up behind dams is a significant source of methane, which is 8-times worse than carbon dioxide as a greenhouse gas. So, hydropower is maybe not that carbon neutral after all.

- Meanwhile, the undammed Mississippi and Ohio rivers are nearing record low levels, hurting barge traffic.

- The U.S. has had twelve $1 billion weather disasters so far in 2023. Hurricane season hasn’t started yet.

Welcome to the end of the newsletter! Here are some apple rankings. I’ve never had a SweetTango, but my favs are HoneyCrisp and PinkLady. Please email me a personal review if you’ve ever had a Newtown Pippin.