How does the rest of the world think about climate negotiations?

Good Afternoon,

Today, I’m going to dive a bit into how the rest of the world thinks about climate negotiations, and how so many differing perspectives tangles up the process.

But I’d also like to remind you about my Kickstarter underway. So far 18 (amazing!) people have chipped in to get me 15% of the way there! Please join my effort to create a new kind of coverage of global climate negotiations. As a supporter, I’ll send you daily reports starting in November, as I prepare to head to Dubai.

Whatever you can do makes a big difference.

-Mike

The basic conceit of the climate negotiation process is that negotiators can’t promise more than what their local politics will allow. While there are 198 parties represented at the U.N. meetings, unlike a representative legislature, the negotiators can’t rely on their own judgment and make agreements on their own, since whatever they agree to, will have to be ratified by their home governments and then need the force of their local laws to ensure they are enacted.

From the perspective of many negotiators, the core problem with the meetings is that nothing significant can get done without the support of the biggest historical carbon emitter, the United States. But even when the U.S. was led by presidents sympathetic to fixing climate change who pushed American negotiators to make bigger commitments, successive U.S. governments backed out of the agreements.

For instance, the Kyoto Protocol, the first major agreement requiring each country to make carbon emissions reductions, was backed by President Bill Clinton in 1997. But it was never ratified by the U.S. Senate, which was Republican controlled at the time of the treaty’s signing. Later, the 2015 Paris Agreement, which required countries to make binding commitments to reductions in carbon emissions, was not sent to the Senate for ratification by Presidential Barack Obama, so when Donald Trump became president, he simply declared the U.S.’s intention to withdraw. When Joe Biden took office, that decision was reversed, but the Paris Agreement remains unratified by the U.S. government, instead it is treated as a policy of the administration. Effectively, it has the force of law so long as Joe Biden is president and can find Congressional funding for it, but as soon as one of those two things changes, the U.S. will be non-compliant.

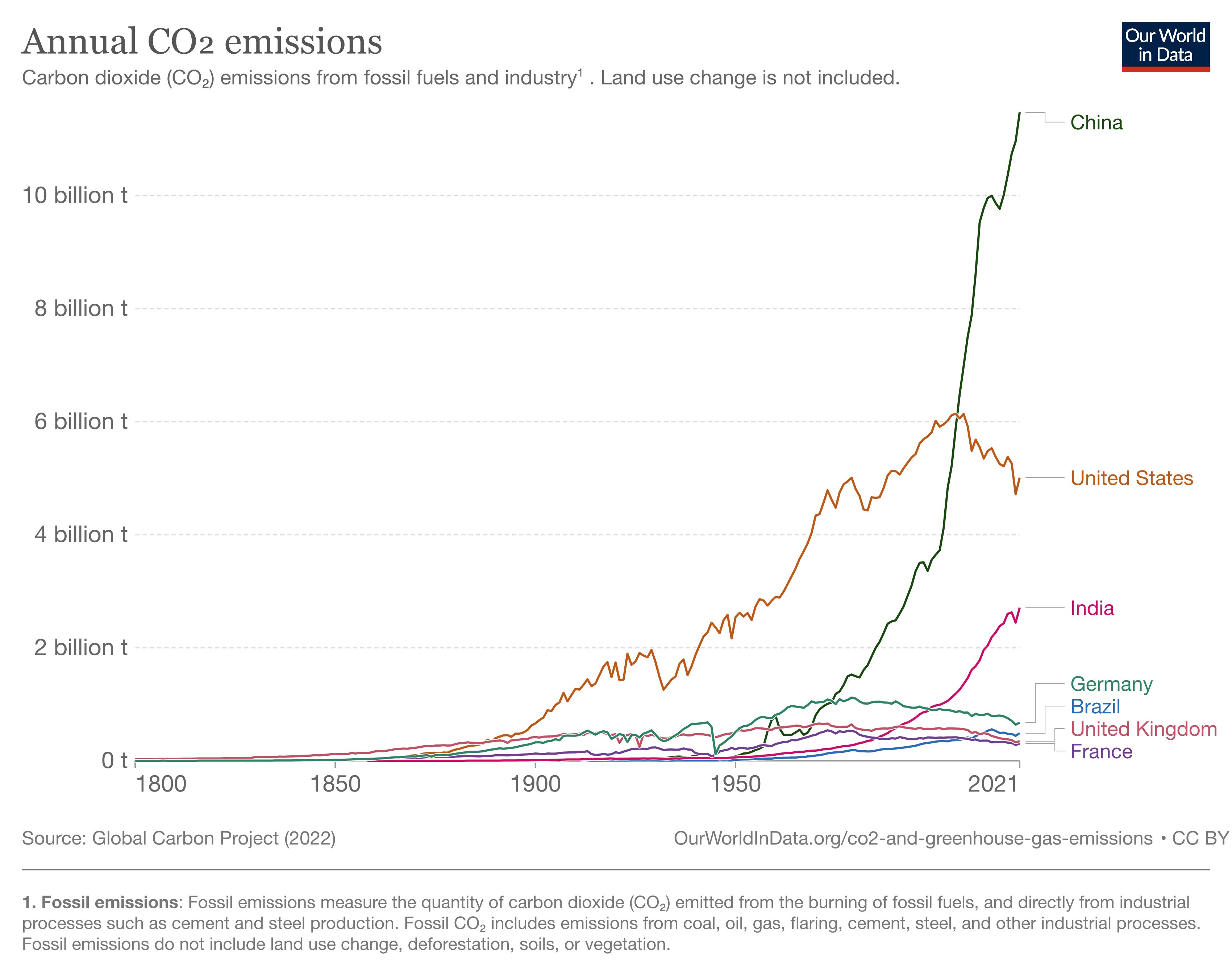

The American wishy-washiness on long-term climate commitments may seem irrelevant within U.S. borders, but at the negotiating table, countries use it as leverage to make fewer commitments themselves. After all, if the biggest historical emitter isn’t doing much, why should China and India, which are currently the first and third biggest emitters worldwide.

What emissions reductions are countries committed to?

As part of the Paris Agreement in 2015, each country made a Nationally Determined Contribution of emissions reductions, while the European Union made a group commitment. While almost every country has made a commitment to change, the vast majority of emissions come from the big four.

U.S. – By 2025, reduce GHG emissions to 26%-28% below 2005 levels

China – By 2023, reduce carbon emissions by 60%-65% below 2005 levels

E.U. – By 2030, reduce net domestic GHG emissions by at least 55% below 1990 levels

India – By 2030, reduce GHG emissions per unit of GDP by 33%-35% by 2030 from the 2005 level.

How are we all doing?

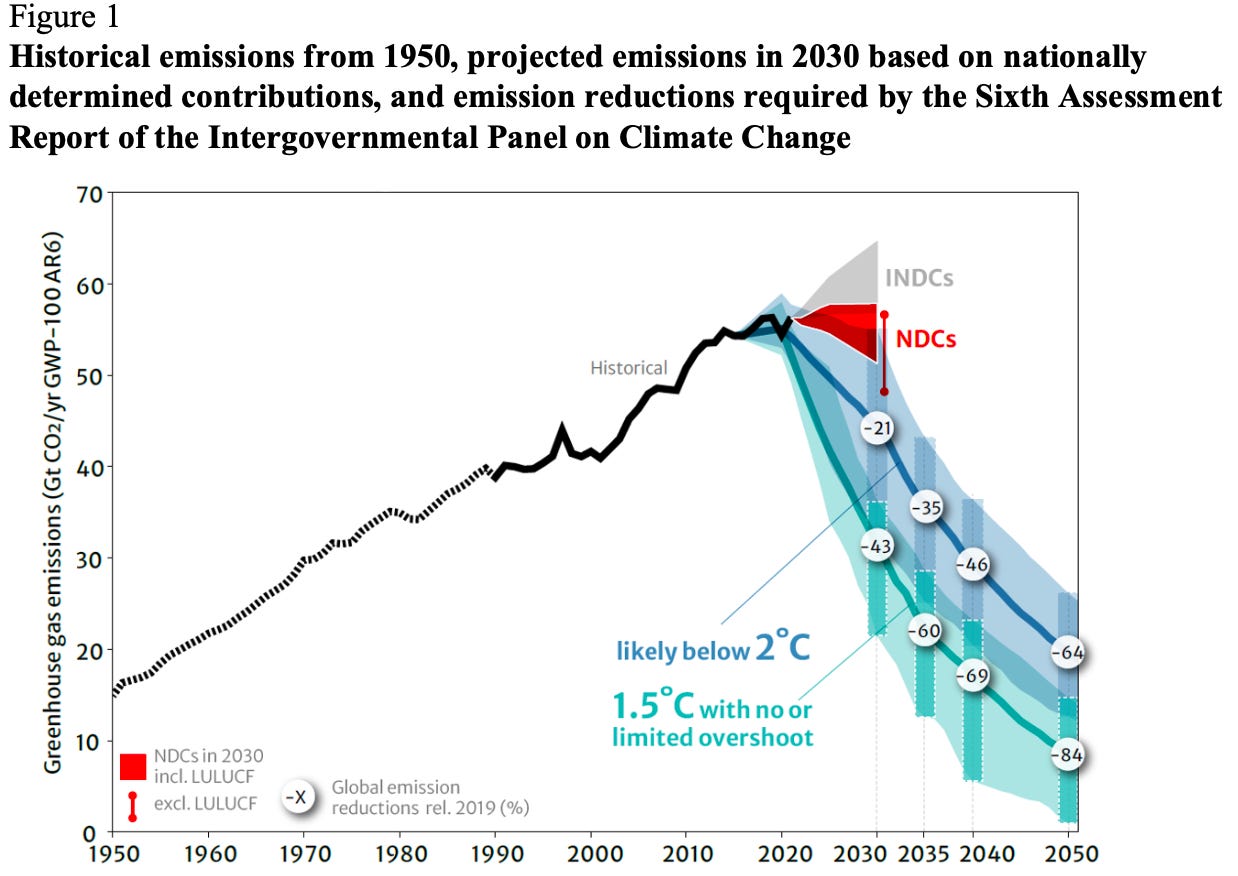

Starting this year, and every five years following, as part of the Paris Agreement the U.N. will conduct a “global stocktake”, where each country’s NDC is evaluated. A final report on each country’s status will be released during the COP28 meeting in Dubai this December. But already, a technical stocktake report released in September assessing the overall status of agreements states that globally, we are nowhere near reaching our goals, and are on track to surpassing 1.5C. (Among some scientists there are concerns that we’re already possibly passing that mark, as last month was the hottest September on record, at 1.8C.)

While we wait for the stocktake, the non-profit Climate Action Tracker does a fantastic job of following which countries are shooting for higher targets, and if their targets are compliant with reaching 1.5C. (Spoiler alert: none of them are compliant)

What are the politics of all this?

Heading into COP28 in Dubai, the local politics of each country sets the tone for what’s possible. In Europe, a Green New Deal to match the Biden Administration’s green energy push seems to be collapsing as the European economy is stalling and national leaders are balking at the cost of promoting green technologies. In addition, Eastern European countries, which are much more reliant on coal than the West, are hesitant to make green energy investments just as their economies are beginning to take off.

China has been building new coal plants at a fast clip, declaring that it won’t peak its emissions until 2030. Meanwhile, it now has the most EV sales in the world, manufactures more solar panels than anywhere else, and announced a plan to build a new nuclear plant every year for the next 6-8 years. So, is it so bad?

Meanwhile, India, eyeing China’s rapid economic growth, has been also building new coal plants, and has resisted efforts to transition from coal to renewables, instead suggesting it could invest in both simultaneously – which won’t result in net reductions in emissions.

As for the U.S., as discussed above, President Biden has proven himself to be a climate warrior, but the world is not confident Donald Trump won’t return to office. Certainly a Trump second term would result in backwards movement on almost every aspect of climate while it is also possible that a more right-wing Speaker of the House, like Jim Jordan or Steve Scalise, would also be damaging to U.S. climate efforts. With those political Swords of Damocles hanging over the U.S., the rest of the world has trouble believing any American promise.

Middling income countries, like South Africa, Iran, and Brazil want to make emissions reductions, but lack the private sector capital to transition to green economies fast enough to reach net zero by 2050. In 2021 at COP26, the idea of Just Energy Transition Partnerships emerged, where teams of rich countries would negotiate agreements to make direct financial investments in middle income countries, which would theoretically attract private investment. However, only a few agreements have been made, with India, South Africa, Vietnam, and Senegal, as negotiations have turned out to be more difficult than anticipated.

Either way, middle income and developing country negotiators are all less focused on reducing carbon emissions – since their economies are still relatively small – and more on attracting financing for green transitions and compensation for damage from climate-fueled disasters, as I discussed last week..

Ultimately, it seems like the upcoming negotiations will be less focused on how much emissions we should cut, and more on how to finance all the work that needs to be done. I’ll address more of that next week.

You made it to the bottom! “Anger is most powerful emotion by far for spurring climate action, study finds”